Periodically, people on twitter will (only half-jokingly) claim that Godzilla is Catholic because the special-effects director for many of the franchise’s classic movies, Eiji Tsuburaya, was Catholic. I’ve vaguely touched on some of these religious topics in other articles, but haven’t really sat down to write a single piece explaining my thoughts in more detail. This, of course, is a glaring oversight for a blog run by a practicing Catholic with a deep love for the Ultraman franchise and kaiju in general. As an apology for the lack of updates over the past year, I’ll attempt to rectify that mistake, and explain some of the most significant connections between these franchises and the Catholic theology with which I’m most familiar.

To summarize, Ultraman and Godzilla are Catholic, but not in the way my readers might think.

First of all, when you get down to it, everything is Catholic because “catholic” itself means “universal”. In addition to that, Jesus Christ reigns as King of the Universe at the right hand of the Father, the Word through which all of creation was brought into existence and is sustained –

But that point is quite a bit beyond the scope of this article.

Instead, my goal here isn’t to evangelize, but to apologize – that is, to explain some specific tenets of Catholic teaching and how they relate to key themes found in both Godzilla and Ultraman stories.

My jokes about preaching aside, the connection between Catholicism and kaiju-related TV series and movies does have a serious basis. Eiji Tsuburaya was indeed a Catholic, who converted when he married his wife. But over the last couple of years, I’ve noticed a pattern of people attempting to link almost all the uses of religious imagery in Godzilla or Ultraman franchises specifically to Tsuburaya’s direction and influence. Many times these connections seem only speculative, and these tenuous stretches do a disservice to his real legacy within science fiction storytelling.

In the case of the original 1954 Gojira, this claim regarding his influence over the movie’s themes and writing is especially shaky. Tsuburaya did submit a very early script for Godzilla, but he didn’t write the final movie. (His version had a giant octopus, for example.) Tsuburaya definitely deserves credit and accolades for his effects work, but I don’t know if his influence, or even his religious beliefs, had an impact on the movie beyond that.

Other common claims point out appearances of religious imagery in Ultraman, but many of the most well-known ones seem to be incidental (Ultraman’s Specium beam pose with crossed arms, for example), or are found in shows made after his death in 1970.

However, this would be a very short article if I just stopped there, dismissing all the claims theorizing how Tsuburaya’s Catholicism influenced his work in kaiju cinema. It’s equally as implausible that his religious beliefs – beliefs which were strong enough to lead him to convert as an adult – had no influence on that work. I do believe there are some crucial connections to be drawn between Tsuburaya’s work on Godzilla, the Ultraman franchise, and Catholic theology. But I also feel like the discussion around this topic often misses the forest for the trees. The critical analysis I see most often tends to focus on superficial details and aesthetics, while overlooking a more powerful and coherent religious reading of these properties.

To be a comprehensive reading of these properties, it should begin, obviously, with Godzilla. The big G. The OG. The most famous kaiju around the world; he has represented many, many different allegories for various evils in our world – disasters, chaos and conflict – but sometimes represents heroic courage as well. In most of his most recognizable appearances however, Godzilla consistently represents things beyond understanding; things that are too huge, too powerful for humanity to control.

Godzilla, in the original movie, is a very obvious allegory for the dangers of nuclear weapons, establishing a now long-running theme of “waking up” a threat which humanity can no longer control. Once summoned by humanity’s mistaken meddling in forces beyond their control, the threat Godzilla represents will overpower any attempt to stop it, or even slow it down. The only response is to face the consequences of those mistakes, and accept responsibility in order to avert future disasters.

That theme has only been expanded to terrifying extremes in modern versions of Godzilla, such as Shin Godzilla. In 2021, Singular Point also made use of a similar idea of “waking up” an uncontrollable disaster. In that series, however, instead of allegorically using Godzilla’s nuclear apocalypse to represent a crisis borne out of scientific progress, the show portrays a crisis of science itself.

What happens when one’s understanding of the laws and mechanics governing the universe breaks down? At what point does knowledge itself become a weapon, something that dismantles the framework – the schema – by which human beings learn about the universe around us? Singular Point goes in a decidedly abstract direction by using the idea of ideas themselves as something huge, terrifyingly powerful, and destructive.

All of these are important questions, but what might any of this have to do with Catholicism specifically? What unique insight into these disasters, man-made or otherwise, can a Catholic interpretation provide us?

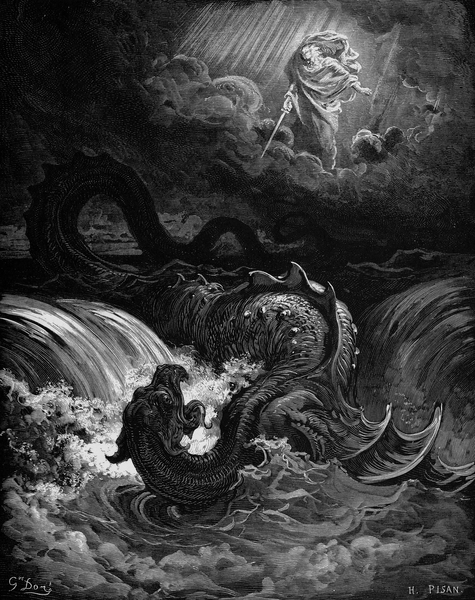

To illustrate that interpretation we need to go past the origins of Godzilla, and into the origins of giant, terrifyingly primordial monsters themselves. Allow me to introduce one of the oldest “kaiju” mentioned in the Bible: the Leviathan.

This mythical creature is mentioned a few times in the Old Testament, but the oldest use of this name comes from the book of Job:

“May that night be barren; Let no joyful outcry greet it! Let them curse it who curse the sea, the appointed disturbers of Leviathan!”

Job 3:7-8

For readers who aren’t familiar with Job’s story, the book is a dramatic play illustrating one central part of Christian theology called “theodicy”, or more colloquially, “The Problem of Evil”.

Or, even more colloquially, “Why do bad things happen to good people?”

Or, “Why does God allow bad things to happen to good people?” as is the case in this story.

Job is faithful to God, but God allows Satan to test him by taking everything away from him. His money, his home, his loved ones, and eventually even his health is lost. Job’s friends leave him, assuming he must have secretly committed some grave sin to earn such a punishment. Job’s wife goes further and tells him to “curse God and die”- but Job doesn’t. But he does complain.

Understandably so, I mean.

When Job demands an answer from God, God shows up and delivers His longest speech in the entire Bible. The references to Leviathan in Job fit into this monologue from God. They challenge Job to account for, and measure the full, fathomless breadth of creation, including the Leviathan.

The verse from Job 40:25 asks, “Can you lead about Leviathan with a hook, or curb his tongue with a bit?”

Job himself, of course, cannot. But this does raise an interesting question – why does the Leviathan even exist in the first place? Why did God make it part of creation?

This is closely related to the central problem of the story of Job itself. If such a terrifyingly destructive beast exists within God’s creation, why does he allow such destruction – and the suffering that results from its destruction – to persist? What purpose do natural disasters and tragedies serve in God’s creation?

Why does Godzilla exist?

Well, what causes Godzilla to awaken in the original movie? Nuclear weapons testing.

To relate this to Catholic teaching (according to St. Augustine of Hippo, and later St. Thomas Aquinas), humanity’s own sins allow evil to enter the world because these sins work contrary to God’s will. In fact, the English word “sin” itself comes from an older Germanic root that means “to separate” or “sever”. Sin literally separates humanity from God and the proper cosmic order that God presides over.

by Carlo Crivelli

As the saying goes, all things happen for a reason, and sometimes the reason is that you are dumb and make bad decisions. Since God allows human beings free will, that includes the freedom to do bad things, and sin. Thus, pain, suffering, death and all other kinds of consequences enter the world as a result of free will exercised (and misused) by individual humans.

In much the same way, Godzilla, and other giant monsters within the movies produced under Tsuburaya’s effects direction, rise as a response to humanity’s worst mistakes. All of these disasters, following in the wake of the kaiju attacks, are the natural and fitting consequence of humanity’s most horrific sins: nuclear weapons, corporate greed, war on a shocking, industrialized scale, the destruction of nature.

This explanation isn’t the only way to answer the Problem of Evil though. Other theologians also point out that God allows evil to exist in the world not just to punish people, but also to create the circumstances to produce mighty works that glorify him. The Biblical story of Exodus is a good example of this. Within that narrative, God purposely makes an example of Egypt to show his power in an unmistakable, historic way.

The Leviathan of Job’s story, along with Godzilla and other kaiju, can also serve this purpose, to demonstrate God’s awe-inspiring power. Their very existence chastises humanity, but also humbles them in a necessary and fitting manner. Embedded within a society which has rapidly become dehumanized, atomized, and industrialized, losing much of our relationship to nature and creation around us as a result, kaiju serve as a reminder of humanity’s own faults and frailties when compared to the majesty of the fullness of creation.

But while kaiju and other works of nature put us “in our place”, it’s necessary to remember that place is within God’s providence over creation. Humanity is equally a part of that creation, so kaiju and human free will could both be seen as serving the mystery of God’s salvation, working within the natural world, through natural phenomena.

(And sometimes those natural phenomena just look really freaking cool.)

Now, one might wonder when I’m going to get back around to Tsuburaya’s Catholicism specifically. I believe these interpretations of kaiju stories within a framework of theodicy are very central to his work, both in his special effects direction for Toho’s monster movies, but also in his personal projects, with his own studio. I think these personal projects will give readers a more specific understanding of these points, since they are series which Tsuburaya oversaw on a more direct level, rather than only being involved in one part of the process within a larger studio.

When describing his own work, Tsuburaya said,

“My heart and mind are as they were when I was a child. Then I loved to play with toys and read stories of magic. I still do.”

Tsuburaya was indeed Catholic, and I do believe that played a role in how he approached his creative work with kaiju movies and shows. But from everything I’ve read about his work, he never intended these stories to be a specifically coded work of evangelization – at least, not in the way some readers might think of it.

Instead, Tsuburaya describes the wonder of creation with his effects work. It might seem ironic that such a larger-than-life, fantastic depiction of the universe could be used for that purpose, but science fiction often pulls this trick. In order to draw attention to specific elements of reality, or a shared human experience, speculative fiction in general will emphasize or exaggerate those elements, to “push” them to extremes in order to analyze that experience more specifically.

So, what elements of the world are emphasized in Tsuburaya’s work? What does he want the audience to specifically take notice of, and consider more closely?

First, let’s look at the anthology series Ultra Q. This show lays out a wide variety of incidents between humanity and the bizarre and unknown creatures they encounter. These creatures and mysterious forces may sometimes intentionally want to cause harm to humanity – but not always. Some of the stories are more lighthearted and humorous, some are horror stories, and others are a combination of both.

All these episodes – and other Ultra Q and Ultraman series produced later on – are connected explicitly through a concept of “unbalance” to explain these events. Just like with Godzilla, often this “unbalance” represents consequences of humanity’s own fallen nature, their mistakes and sins. In other words, humanity becomes “unbalanced” from the right relationship to creation around us.

Take for example, Peguila, awakened by rising temperatures in Antarctica due to climate change. Or Kanegon, a weird coin-eating monster which embodies the selfish greed of certain human beings. And sometimes there is no reason for these bizarre encounters. Strange things just simply exist in the universe and humanity is caught up in the accidental destruction they leave in their wake. Sometimes, humanity is forced to struggle to merely survive against these threats.

In each episode however, human beings are forced to reckon with how they understand and interact with the world around them. What kind of importance do we place on things like exploration into the frontiers of space, the rush of on-demand production in modern society, simple comforts of housing and luxury, over the consequences such lifestyles may inflict on other lives, both human and otherwise? When the most horrific events literally drop out of the stars, how far will humanity’s courage and compassion stretch before it breaks?

The answers are sometimes simple. After all, Ultra Q and many other shows produced by Tsuburaya are intended for families, an audience of all ages. But they are never easy to face, and many of the episodes end with hard-fought, narrow victories, or simple twists of fate which leave the characters with a fleeting, uncertain peace. Regardless of how the episodes conclude, the initiating conflict, which interrupts humanity’s peace in the first place, always comes back to this idea of “unbalance”, disrupting the connection and right relationship to other parts of creation.

One might be skeptical about this idea being specifically Catholic, but much of the Church’s teaching, from the earliest days of apostolic writings, focuses heavily on the position of humanity within the larger history of the world and the rest of creation. This informs how the Church understands smaller societal structures and their responsibilities, such as a person’s position within a family, a community of Christians, civil society, and even the hierarchical structure of the Church itself. When sin enters the world through either our own actions, the actions of others, or simply as a result of the fallen nature of the world itself, it “unbalances” that proper order and causes suffering and pain as a result.

In fact, religious scholars often draw this concept from even older Jewish teachings regarding the laws of the Torah. To be described as “righteous”, or to seek righteousness in the way understood by 1st century Jewish audiences in the Gospels, meant to behave rightly, in accordance with the laws and teachings established by God for his chosen people. Then-Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) described it in this way:

In Jesus’ world, righteousness is man’s answer to the Torah, acceptance of the whole of God’s will, the bearing of the “yoke of God’s kingdom,” as one formulation had it.

Benedict XVI, Pope . Jesus of Nazareth (p. 17). The Crown Publishing Group.

In other words, we can see “unbalance” as related to an idea of unrighteousness. Conflicts and disasters in the Ultra Q series, as well as many other kaiju works from Tsuburaya, happen when human beings start relating to the universe around us in ways that are contrary to God’s will.

Now, readers might raise an objection at this point, by going back to the story in the Book of Job which I mentioned earlier. In that story, Job faces disaster and suffering even though he is described as being righteous. So, if we do everything correctly, do right by those around us, and care for the universe and the other lives we encounter, why do bad things still happen to the righteous?

As it turns out, there is a third way one could answer the Problem of Evil according to Christian philosophy, and I believe this last way forms the basis of the most recognizably Catholic aspects of the Ultraman franchise.

After Ultra Q proved a success, Tsuburaya expanded further on the idea of exploring how humanity encounters the unknown with the Ultraman series. Even if the series don’t explicitly use the word “unbalance”, this concept has still become an important theme of the franchise, even after Tsuburaya’s death

I’ve often seen a claim stating the earliest concepts for Ultraman depicted him as a villain. As far as I can tell, that’s not true. From the beginning, Tsuburaya favored the idea of humanity interacting with a friendly alien, even before the show was called “Ultraman”. The early concepts for Ultraman’s suit design, however, are obviously more explicitly alien-looking than the final version.

Even with these more inhuman designs, Ultraman was always intended to be a positive character. This concept illustrates a figure who is strange, intimidating, maybe even terrifying in his scale beyond humanity, but is also undeniably benevolent to humanity. Like the concept of “unbalance”, this idea also has grown to become a fundamental part of the franchise even in modern installments, outliving Tsuburaya himself.

These two elements, the concept of “unbalance” and the figure of Ultraman himself as a central, heroic character, lead into our third understanding of the “Problem of Evil”. This third explanation is necessary because, as we see in the case of Job, the previous two explanations often fall short in the face of suffering on a personal level. They fail to adequately justify why a person who is otherwise righteous and upstanding, in balance with their place in creation and God’s will for them, would still be punished by these evils.

Why would God’s will for these individuals still necessarily involve suffering?

To address this third interpretation of the “Problem of Evil”, I first need to emphasize the point that all Christian theology starts with the understanding that God is both all-powerful and all-good (omnipotent and omnibenevolent). Thus, logically speaking, there can’t be any part of God which is lacking, incomplete or not good. God cannot desire evil or suffering because that would contradict his nature as all-good. God also cannot allow these things to exist unopposed simply because he is unable to stop them, because that would mean he is not omnipotent. The only thing that would restrain God is the simple logical impossibility of him contradicting his own nature.

Of course there are philosophers and theologians who argue those points on some level, but this essay is concerned about a Catholic reading of Tsuburaya’s work. We’ll leave the gnostic heretics to their own devices and just look at the orthodox points. So far, we’ve addressed two of them, showing how natural disasters and catastrophes embodied by kaiju can represent either the natural consequences for humanity’s sins, or the awe-inspiring glory of God’s creation which humbles those who encounter it.

Those points aside, this leaves orthodox theologians with only one other alternative that unifies all these principles: the reason why God allows evil things to happen is so that a greater good may come about from it.

This point is no mere afterthought, however. It forms the central mystery of Christian teaching and practice. During the height of Holy Week, the highest days of worship in the Church’s annual liturgical calendar, the event of Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection is represented by the celebration of the Easter Vigil. On the night before Easter Sunday, Catholics celebrate a special long and dramatic Mass to represent this central mystery. At the beginning of this Mass, a specially long and dramatic preface called the Exsultet is also recited to the people. This reading explains the significance of Jesus’ death and resurrection, and how it fits within the larger context of God’s actions throughout human history, from the very beginning of creation.

This idea of evil being allowed to exist so that good might prevail, and not just prevail but be made stronger, brighter, and more gloriously triumphant in that victory, is especially illustrated in a line of the Exsultet:

O truly necessary sin of Adam, destroyed completely by the Death of Christ!

O happy fault, that earned so great, so glorious a Redeemer!

“The wages of sin is death”, according to the Apostle Paul in his letter to the Romans (6:23), and human beings’ mortality and mortal suffering was understood to be a consequence of unrighteousness, or obstinance against God’s will. The “fault” the Exsultet describes is the original obstinate refusal of God’s will, Adam and Eve’s fall in the Garden of Eden. And yet, in a seeming paradox, it is that same fall that brings about something even greater in the full perspective of God’s salvation. Humanity lost the Garden of Eden, but gained “so great, so glorious a Redeemer”. The very mechanism by which humanity has been chastised – death, even death on a cross – becomes the way we are reunited to God’s will, the new path of righteousness.

Some readers might be wondering about the purpose of this proselytizing, but trust me, this is related to Ultraman in a few important ways! First of all, there’s the way the series itself opens and closes – with death.

The first episode of the original Ultraman series begins with a pattern of events similar to Ultra Q. The Earth is faced with a seemingly-random disaster that arrives from the stars, two aliens crash on the planet and drag a conflict with them that could overwhelm humanity’s ability to defend itself from the terrifying fallout. This disaster is compounded by personal tragedy, when Shin Hayata, a pilot with the scientific research and defense organization, the SSSP, is killed in the crash by accident.

But there’s a twist this time, and the story develops in a way that marks Ultraman as a new development from both Ultra Q and other contemporary kaiju media. Rather than simply accepting Hayata’s death as a necessary casualty, Ultraman instead chooses to give his own life to the young human.

This not only brings Hayata back to life, but also gives him the power to use Ultraman’s own huge size and strength to fight against Bemular, and other monstrous threats the characters face throughout the show.

In this way, a great disaster that might have only brought suffering instead gives humanity a hero, a way to protect the planet and the lives on it from further disasters. The mechanism by which terror and destruction is brought to the Earth – in much the same way we see happen in other kaiju shows and movies – becomes humanity’s hope for overcoming it.

To take this theme even further, there’s another death the show grapples with, of Ultraman himself in the finale. After fighting to his limits, Ultraman falls in the battle against Zetton.

This might have been humanity’s darkest hour, after watching their hero and champion defeated by this alien invasion. However, in another twist of paradoxical salvation, this becomes humanity’s greatest accomplishment because the SSSP defense team goes on to defeat Zetton with their own courage and technology.

In both examples, we see suffering and death, the “evil” that is wrestled with when considering the “problem of evil”, lead to even greater victories. The characters of these stories are made stronger as a result of their struggle through these trials. The eventual victory they achieve over that darkness is more joyous, and poignantly powerful because they faced such terrifying challenges.

This concept strongly echoes something that J.R.R. Tolkien referred to as “eucatastrophe”. The word comes from both the Greek “catastrophe” meaning a sudden turn of fate, and the prefix “eu-” meaning “good”. He described it as follows in one of his essays,

“The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous “turn”… it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

“On Fairy-Stories”, 1947

Tolkien understood the purpose of these types of joyous twists of fate in stories as a sort of consolation for the readers, to give them hope against dark circumstances they might find in their own lives. Personally, I hear a lot of similarities to how Tsuburaya describes his own work, “stories of magic”. That magic comes from a child’s perspective, but it’s far from childish, instead it perseveres through trials, disappointments and struggles that every adult faces in their life.

Going back to theology, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ is itself a eucatastrophe, and more importantly within Christian teaching, it is the eucatastrophe that makes all others possible. Tolkien himself even makes that point in both the essay “On Fairy-Stories” and in later letters.

But this sudden turn of death into new life isn’t the only theological connection to be found in Ultraman, and my last point rests on the reason why the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ himself is so specifically central to Christianity.

An essay fully addressing the theological subcategories of soteriology and Christology along with my amateur attempts at theodicy would be beyond my reader’s patience, probably. So I will summarize just one key point here as it relates to Ultraman.

There are many stories that end with ironic twists which lead to happy endings, and many of those endings can be found in other kaiju shows and movies, and Tsuburaya’s work in that media. What truly distinguishes Ultraman from other kaiju stories, or even from other science-fiction stories as a broader genre, what initially attracted me to the franchise, and what has fascinated me as a fan for the past seven years, goes beyond that.

I’ve explained how Ultraman has a special concern for humanity’s place in creation, and how human beings serve their rightful, appointed responsibilities in that place, emphasizing both the wonder and the terrifying power of God’s appointed creations. I made the point that Ultraman also emphasizes fundamentally hopeful and joyful stories even in the face of those terrifying challenges. But more than the emphasis on righteous harmony with creation, more than the emphasis on joyful twists of fate, there is one last point that has given Ultraman a powerfully, uniquely Catholic identity for the past 56 years.

And that is the hypostatic union established by Ultraman himself.

“Hypostasis” is more Greek, this time referring to the “underlying state” of nature or reality, the fundamental “stuff” that gives something its identity.

More specifically in orthodox Christian theology, the “hypostatic union” represents the fact that Jesus Christ is both fully divine (with the same elements I described above, all-powerful and all-good), but also fully human, and shares completely in both natures without either being restrained, limited or negated in that union.

This point is so important to Catholic teaching that multiple Church councils have convened through history to argue and refine it over the last two thousand years. This is why Saint Nicholas punched the bishop Arius in the face, after Arius’ teaching denied the fully divine nature of Christ.

While the in-depth explanation of this concept and its full ramifications for Christian practice would fill multiple thick leather-bound books, one of the best analogies I’ve found for illustrating it to the average person is with Ultraman.

I have to put a few disclaimers on this point, the main one being that Ultraman himself is definitely not God, is not portrayed as God in the shows, and this is an analogy, not a full dogmatic explanation of the concept. If Saint Patrick can be allowed a little leeway with his shamrock metaphor, then I ask that my readers give me the same benefit of the doubt before I get accused of heresy or sacrilege.

As I mentioned earlier, while Ultraman was always intended to be a benevolent figure, the original concept for the series depicted him as much more alien in appearance. Even the Shin Ultraman movie borrows from early concepts, making his appearance more distorted with odd proportions that emphasize this alien origin. This helps set up the eucatastrophe of the franchise, going against expectations. The alien monster that arrives on Earth turns out to be friendly and generous towards humanity, and goes to astoundingly selfless ends in order to protect them from other alien threats.

However, the franchise goes one step further by uniting a human life with Ultraman’s own life in a specifically literal way.

The show never really explains how this happens on a scientific level, but by giving his own life to Hayata in the first episode, Ultraman becomes united to that life, and both of them function essentially as one person with two natures. As a result, Hayata as Ultraman acts as a go-between, a mediator between humanity and the wondrously strange universe that humanity encounters.

This idea of Ultraman representing both humans and aliens, mediated by one person, is explicitly referred to in the show itself. The evil alien Mephilas is confounded by this union in the episode 33, “The Forbidden Words”, when he asks if Hayata is “human or alien” and Hayata responds by claiming he’s both. The audience can also see this role of Ultraman as a mediator in how he allows humanity to understand its rightful place in the universe, and how to address the parts of creation that human beings might unjustly fear or despise.

This second aspect of a mediator – to suffer as reparation for humanity’s own sins, thus re-mediating them – becomes an especially tragic point in episode 23, “My Home Is Earth”. This episode calls back to the idea of kaiju disasters representing the sins of humanity again, but with additional personal tragedy. The kaiju itself was once a human, sacrificed by callous decisions, and twisted into a monstrous threat as a consequence of the wicked – unrighteous – politicians who demanded his death and the subsequent cover-up.

Another tragedy, which ends in a eucatastrophic ending this time, occurs in episode 35, “The Monster Graveyard”, in which Hayata and Ultraman both consider their role representing both humanity and alien life, and the consequences of their actions over the course of the show.

Rather than merely allowing humanity to triumph and stand superior over other lives for their own sake, these more tragic episodes reorient Ultraman’s role. By protecting humanity, Ultraman restores the “balance” or righteousness of the universe, ensuring humanity’s right relationship to God’s creation. This isn’t accomplished by simply leaving humanity to be destroyed by the wages of their sins, nor is it accomplished by destroying all other life in the universe and elevating humanity to godhood through their own merits.

In fact, throughout the franchise, Ultraman rarely triumphs over evil only by fighting and destroying threats. If that was all Ultraman represented, then humanity might become complacent and only rely on him as a weapon. The original series heavily emphasizes this problem, especially in stories like episode 37, “A Little Hero”, but a more relevant example is found in the finale.

The final episode of the original series ends with Ultraman giving his life in the fight against Zetton, and the SSSP using their own technology to fight in his place and defeat the invading alien threat. But humanity doesn’t achieve that victory separately from Ultraman, or in spite of his failure. Rather, it’s Ultraman’s example which inspires them, to give them the courage to overcome this latest disaster and bring out the characteristic eucatastrophe that provides the happy ending to the show.

The role of Ultraman as a mediator goes both ways. As a hero, he allows humanity to face the unknown with courage, compassion and hope, but also provides a path by which humanity can imitate and embody that example for others. Ultraman may look like a weird fish-faced silver alien who shoots laser beams out of his hands, but human beings can recognize and relate to him because he also intimately knows the experience of being human. Regardless of whether the Ultraman of each series binds their life to an individual human, or adopts a human identity of their own, they choose to live alongside human beings as a human. In this way, a sort of kinship develops between Ultraman and humanity, adopted brothers and sisters, a community united by this same shared desire for righteousness.

That relationship forms the fundamental power of Ultraman, and because humanity participates in that relationship, the power of Ultraman becomes something that all people can share in. The franchise is very consistent about the idea of ordinary people serving as “Ultraman” by emulating his courageous self-sacrifice and compassion, even if one doesn’t have the ability to also shoot laser beams out of their hands.

Relating it back to Christian teaching, this powerfully represents how the Church understands not just the hypostatic union of Jesus Christ’s dual natures, but how human beings participate in the mystery of this union. When someone is baptized, we say that they are adopted into the body of Christ, and share in that divine nature, in the same mysterious way that Jesus relates to God the Father. In other words, (borrowing from Pope Benedict XVI again), we can know the will of the Father, the path to righteousness because we know his Son.

The same light that gives Ultraman his strength and powers can be understood as divine grace, the shared mystical connection between the Father and Son. (Which I could characterize as the Holy Spirit in this argument. Maybe. Someone’s probably going to point out I’ve committed heresy regardless.) Fittingly, this light is often referred to in the Ultraman franchise as the power of “bonds”. I’ve limited my discussion of these theological implications to the original Ultraman series, but the 2004 series Ultraman Nexus gets really deep into this metaphor in a unique way.

Speaking of limiting my discussion, I think I need to start wrapping things up.

Going back once again to my original argument about theodicy, Ultraman is unique among other kaiju movies and shows because he represents a moral framework for humanity’s response to the Problem of Evil. Even if my readers aren’t Christian, I hope they can take away the importance of this example of virtue, and how Ultraman’s intimate relationship to humanity allows human beings to respond to and emulate that example in a specific, personal way.

The universes in which Godzilla and Ultraman exist both serve to humble the human beings caught up in these larger-than-life events, to emphasize their smallness amidst the full, awe-inspiring diversity and scope of creation. But rather than just overwhelming humanity, shrinking the human experience into insignificance against the huge scope of these stories, the best kaiju stories give human beings an active role within that universe, which we are responsible for. Many of these kaiju movies, not just Ultraman shows, often depict the human heroes as individuals who act courageously to protect the lives they can, usually in seemingly small ways, in the middle of these terrifying disasters.

Ultraman shows also emphasize these small acts of courage, but it takes that depiction of righteous virtue deeper into themes and symbols that are Catholic in a far more obvious way. And I don’t mean “obvious” in the sense of “Did you know that Ultraman holds his arms in the shape of a cross” or making a montage of every time Ultra heroes get crucified in this franchise. (Although to be fair, I considered that for a minute.)

But that kind of reliance on hidden symbols turns Catholicism into a sort of scavenger hunt, a Dan Brown-esque cipher only recognizable to those who have the correct knowledge. Instead, I believe the reason why Ultraman has become such a recognizably heroic figure, is because the allegories the franchise use are plainly obvious, even if you’re not Christian at all!

Repeating what I said at the beginning of this essay, it seems like commentators who try to emphasize Ultraman’s religious symbology often miss the forest for the trees. The influence of Catholic theology on Ultraman is not just limited to obvious visual metaphors like our heroes getting crucified. Instead, it is the example of Ultra heroes themselves, how they choose to fight, why they choose to fight, and what empowers them to achieve meaningful victories in those fights.

Even without the Christological allegories, that example stands out to all audiences, regardless of their religious background or lack thereof. The virtues that Ultra heroes all demonstrate, the courage, kindness, hope and charity that defines their strength, are all recognizable and valued by humans across all belief systems and religions.

However, I also don’t want to downplay how closely Ultraman’s depiction of these virtues align with how Catholics and other Christians understand theological virtues derived from grace. The key difference is that grace, the light that Ultraman represents, is never earned or demanded by one’s own merits.

Human beings participate in divine grace, and are adopted into it. Left alone, humanity cannot merit it only with their own righteousness (nobody’s perfect all the time!), but grace is something greater than a simple equivalent transaction – it is a gift.

In the very first episode, Ultraman had no reason to give his life to Hayata. He gained nothing by it, required nothing, and asked for nothing in return. The only way one could possibly respond to a gift of that magnitude is with gratitude, to “pay it forward” as it were. And that is exactly what Hayata, humanity as a whole, and every other protagonist and group of characters – even the Ultras themselves – have all continued to strive for in every single story across the franchise.

When talking about religious influences in these shows and movies, I could post screencaps of crosses and crucifixions, bring up kaiju names taken from the Bible, or references to the apocalyptic book of Revelation.

But that’s not why I fell in love with kaiju stories.

For me, personally, as a Catholic, the most powerful way both Godzilla and Ultraman have impacted my life is through the simple, unyieldingly virtuous examples of the franchises’ heroes, against such terrifyingly huge and awe-inspiring disasters. And in the case of Ultraman specifically, it is the way that the franchise links the virtues of its heroes with participation in grace, divine love, freely given, unmerited, gained through the death and resurrection of God Himself made man, that we are made righteous in accord with God’s will.

More than the crosses, Bible quotes and apocalyptic battles, that is what a Catholic reading of Tsuburaya’s work should emphasize.

I know I said I wasn’t going to evangelize, but hey, if the franchise is going to play its metaphors so plainly obvious, why shouldn’t my conclusion for this essay do the same?

In conclusion, it’s very easy to get too wrapped up in legalistic details when discussing religion, but being Christian, and being Catholic isn’t just about having a vocabulary with the biggest theological words. Living a Christian life is about active participation in a relationship with God, rather than only for ones’ self, and Tsuburaya’s work in both Godzilla and Ultraman help to continually remind me of that fact.

If nothing else, I hope this article helps some of my readers understand that as well.

Credits and Copyrights:

All images pulled from Godzilla and Ultraman are credited to their official licensors and distributors.

Production images of Ultraman and photographs of Eiji Tsuburaya were provided from Ultra Blog DX, “Ultraman (1966) Production History” and the sources and credits provided there.

All religious artwork and images credited as written.