Author’s Note: Another post I’m porting over to this blog, this is a commentary that ties a lot into heroic narratives that I enjoy, and I’ll probably refer back to many of these ideas when I start delving more fully into toku shows and other superheroes.

“And I shall shed my light over dark evil”

One mistake I see a lot of people make when they talk about superheroes is by thinking of heroes and their villains in terms of a sort of Zoroastrianistic duality. In this, good and evil are represented as two necessary halves of each other, and one cannot exist without the other. This is the theory that Lex Luthor would not exist without Superman, the Joker without Batman, using the metaphor of shadows requiring light to be cast first before they appear.

What this misguided line of thinking assumes is that without a hero to press and challenge them, supervillains would merely evaporate like smoke and trouble no one anymore. Of course, in reality, we know that is not true at all, evil exists whether or not there is a force of good to oppose it, and without good men to challenge that evil, it merely grows, instead of retreating away.

Lex Luthor would still be a corrupt, petty industrialist without Superman (for all his grandiose claims, whenever Superman goes missing from the Earth, Luthor simply sets about taking over the world rather than curing cancer or solving world hunger). Similarly, the Joker would still be a murderous crazy person without Batman, although likely the more banal, familiar (yet even more uncomfortable) form of criminal insanity that shoots up movie theaters instead of constructing ludicrous plots to rob banks and poison whole cities.

Most falsehoods that we hear, however, originally arise from an underlying fundamental truth that is distorted somehow. In this case, the idea that the conflict between good and evil shapes each side as they react and interact with each other. In fact, many sets of heroes and their prime nemeses share a lot of things in common, so by comparing them to each other, certain things about their respective characterizations can be revealed. George R. R. Martin, author of the “A Song of Ice and Fire” series, as well as documented longtime Marvel fan-boy, just had a published blog post of his own where he talks about how the Marvel movies over-use this trope. In his words:

“…I am tired of this Marvel movie trope where the bad guy has the same powers as the hero. The Hulk fought the Abomination, who is just a bad Hulk. Spider-Man fights Venom, who is just a bad Spider-Man. Iron Man fights Ironmonger, a bad Iron Man. Yawn. I want more films where the hero and the villain have wildly different powers. That makes the action much more interesting.”

I, in fact, disagree pretty strongly. The whole reason why this is a common storytelling convention in any sort of heroic narrative (I will be touching on the concept a lot when I start writing about Kamen Rider series, for example) is because when both the hero and the villain have similar powers from similar places, it makes it easier to draw distinctive aspects of their characterizations based on how they make use of that power. And in my personal case, it’s this distinct dichotomy that allowed me to grow to appreciate one superhero within DC that I never really paid much attention to before: Hal Jordan, the Green Lantern.

In Brightest Day, In Blackest Night…

You see, one of the most common jokes about Hal Jordan is that he is a joke. A flake. An idiot, sometimes even. He’s not as strong or as idealistically kind-hearted as Superman, he’s not as smart or resourceful as Batman, he’s not as unfailingly optimistic as his best buddy, the Flash even, so why is Hal a member of the Justice League? What can he do that the other superheroes can’t? Why should we care about him? I found myself asking this a lot when reading through certain DC stories because while I understand and enjoy several other Green Lantern characters (Alan Scott, Guy Gardner, Kyle Rayner even), I never got why Hal was supposed to be “the best”.

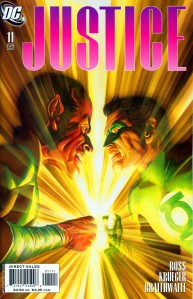

That changed when I sat down to read the 12-issue miniseries Justice by Jim Krueger, Alex Ross, and Doug Braithwaite. A story with only questionable continuity within the DCU, published between 2005 and 2007, it was meant to be a sort of throw-back to Silver Age comics, using the Justice League lineup and associated characters from those days, facing off against their classic villains. In practice, it winds up being the biggest, most epic, best episode of Justice Friends ever conceived. It’s a lot of fun all around, and features some of Alex Ross’ best artwork in comics as far as I’m concerned. But one section that really sticks out in my mind is actually Hal Jordan’s subplot within the series.

To make a long story short, the Justice League’s villains all conspire with each other to assassinate, incapacitate, or otherwise remove the League’s members from play in order to carry about their ultimate plan to relocate Earth’s populations to their own little spheres of influence, promising the citizens that they are their only chance to avert an oncoming disaster that will destroy earth. In the process, Sinestro uses a Boom Tube (think super-advanced space-magic that can transport you anywhere in the universe instantly) to send Hal Jordan to the furthest reaches of uncharted deep space, where there is no hope of rescue. Hal Jordan is left there, assumed to be as good as dead once his able-to-do-anything-imaginable ring runs out of power.

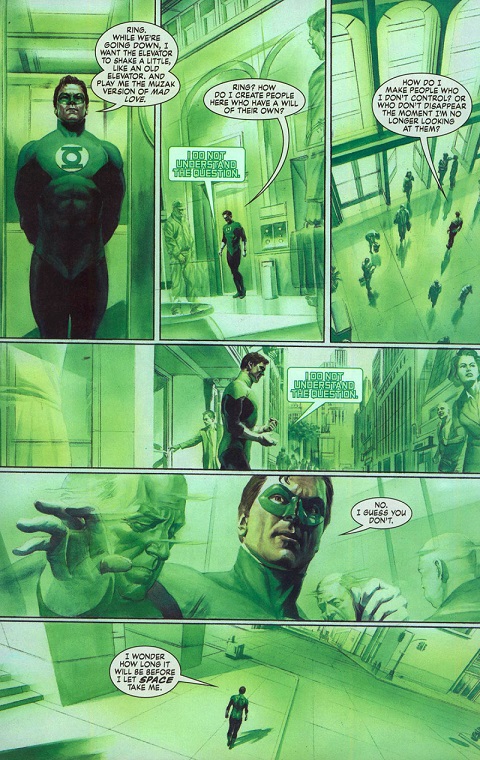

In order to keep him alive, the ring transforms him into electrical impulses to be stored within the ring, his consciousness kept alive with minimal power indefinitely. However, again, with no hope of rescue beyond even the reach of any starlight, he is left within the world of ring, a realm where he can do anything, be anything, but is completely, utterly alone, for eternity.

Inside the ring, everything is shaped by Hal’s own experiences, his ideas, ideals, and most importantly, his willpower and imagination. But try as he might, Hal cannot create real, self-autonomous beings with this power.

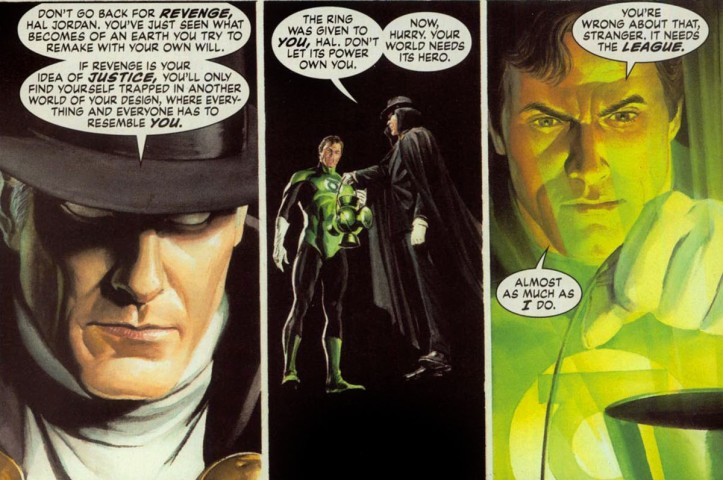

Everything is ultimately a reflection of his own self, when he talks to them, they tell him what he wants them to say, and disappear as soon as he turns away from them. He has created a kingdom that is populated by facsimiles of himself, a realm of things to be used, not people.. And it nearly drives him completely insane, but luckily not before the Phantom Stranger shows up to bring him back to earth. (Appearing out the blue to help the League when they have no help or recourse left is what the Stranger specializes in, after all.)

No Evil Shall Escape My Sight…

So what does this have to my original point of comparing the use and abuse of power by heroes and villains? Well, all this leads up to Hal Jordan confronting Sinestro again on earth in a climactic battle, but with a catch, he’s not using his own Green power ring. As part of the heroes’ schemes, Hal is forced to use the yellow ring that Sinestro himself uses and draws power from. And this is connected to the ordeal that Hal has just been through, Hal basically has experienced exactly what the villains have planned, to take people and shape them into not people, but reflections of themselves.

This is what villains do, they use power not for the benefit of others, but to enforce their own mind to recreate the world around them in their image, their likes, dislikes, opinions of justice or fairness (or lack thereof). Sinestro, along with the rest of the Legion of Doom, doesn’t see a world of people, they only see things to be used. And as Hal himself says, it’s because Sinestro put him through that ordeal that he realizes the difference and will never fall into that trap himself.

….Yeah I know, hugely ironic considering Emerald Twilight, but keep in mind this story is essentially an out-of-continuity Elseworlds tale. I’ll save the analysis of his fall and redemption through his role as the Spectre for another article.

Ultimately, while I said that the idea of the hero and the villain sharing a power source or other elements in common is very ubiquitous in superhero stories and other heroic narratives, the comparison between Hal and Sinestro illustrates one aspect of that conflict, and that is the purpose of leadership. Hal Jordan was the best Green Lantern because of his leadership abilities.

The simplest way to illustrate this is through his characterization in the woefully short-lived Green Lantern animated series. In that series, he’s very much of a Captain Kirk-type character, who leads from the seat of his pants and knows when to overlook rules when they become obstructive to the best good for others. In comparison, Sinestro is most strongly associated with fear, he rules through intimidation. While he may be a sympathetic and tragic figure at times, ultimately it’s the fact that he sees his power to be used in order to enforce his very, very strict and merciless brand of justice on the universe that sets him apart.

The simplest way to illustrate this is through his characterization in the woefully short-lived Green Lantern animated series. In that series, he’s very much of a Captain Kirk-type character, who leads from the seat of his pants and knows when to overlook rules when they become obstructive to the best good for others. In comparison, Sinestro is most strongly associated with fear, he rules through intimidation. While he may be a sympathetic and tragic figure at times, ultimately it’s the fact that he sees his power to be used in order to enforce his very, very strict and merciless brand of justice on the universe that sets him apart.

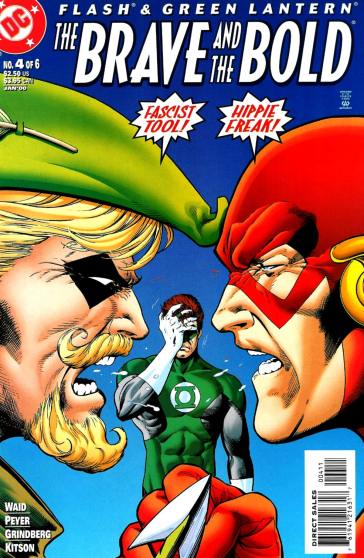

Hal understands that in order to be a good leader, he needs to be able to trust his comrades-in-arms to make their own decisions and bring their own talents to the table, rather than controlling them into only doing what he wants them to do. He balances this well on earth with both his friendships with Barry Allen, the Flash, and Oliver Queen, the Green Arrow. One is a down-to-earth, responsible, friendly optimist, and the other is a brashly outspoken bleeding heart liberal, both are diametrically opposite to Hal’s own personality at times, and yet they all bring out the best in each other through their friendship and work well together.

(Er, well. Most times.)

Hal can be a goof at times, but I like to think that ties into his leadership too, he doesn’t try to control people to be something else because he understands that he’s not perfect himself.

Some people question why superheroes don’t try to rule the earth as a benevolent dictatorship if they really want to solve the world’s problems. In reality though, that’s how villains think, not heroes.

[…] are closely connected, either through shared origins or powers. (I discuss it at length in a previous article in dealing with Western comic book superheroes). Emu had to rein in M by taking that competitive spirit and tempering it with an understanding of […]

LikeLike

[…] interact that was not borne from his own creation. (Note: I write more heavily about this theme in my article about Green Lantern and Sinestro from a couple years back. It’s a surprisingly common recurring villain […]

LikeLike